In a break from my normal practice, I am dividing today's range report into two parts. In this one, I will discuss my efforts to replicate the military's M1873 cartridge in .45 Colt (remember, there's no such thing as .45 Long Colt). I should start by saying that a perfect reproduction is impossible, for several reasons, as will become apparent below; rather, this is my attempt to reproduce the cartridge as closely as I can using modern brass and priming with an eye toward at least getting the external ballistics right.

|

| Fig. 1: Early military .45 copper Colt cartridges with the Benet primer. (Left, M1873 Colt, center and right, Schofield .45 Short Colt.) |

|

| Fig. 2: The M1873 Cartridge after Kuhnhausen 2001. |

The M1873 is the first of the .45 Colt metallic cartridges used by the U.S. military. They were made of copper rather than brass and employed a rather unusual priming system called the Benet primer invented in 1866 by Stephen V. Benét. This system included a small cup containing fulminate of mercury (see figure 1 above) which was crimped inside the copper case. From the outside, this looks like a rimfire cartridge, but as the picture above shows, it is not.

The ball used in the M1873 weighed between 250-255 grains, and had two grease grooves and a hollow base (see figure 2 above). This was loaded over 30 grains of 2F black powder (yes, 2F, that is not a typo).

|

| Fig. 3: Comparing the Accurate Bullet Mold bullet (left) with the original design (right). |

In order to replicate the bullet used in the M1873 cartridge I contacted Accurate Bullet Molds for a custom mold. The mold they provided yields a bullet which is very close to correct, but differs from the original in two respects (see figure 3 above). First, the Accurate bullet has a crimp groove while the original does not, and second, the original has a hollow base, which my bullet does not. The originals didn't use a crimp groove for reasons which are obscure, but appear to be related to the difficulty of mass production of metallic cartridges in period. The hollow base can't be easily replicated by the method Accurate Bullet Molds uses to make their molds since it requires a special insert, but it turns out to be unnecessary. The original bullet was .452 (to make it easier to load into early loading machinery) and it was felt that the hollow base would be necessary for the bullet to obturate into the rifling, but the Accurate bullet is .454 and doesn't need to obturate for proper fit so there is no need for a hollow base. The Accurate bullet is .454 in diameter and weighs approximately 255 grains.

I load my cartridges into Starline center-primed brass cases (incidentally, the civilian version of the 1873 cartridges were brass and had center primers, much like mine). To read about how I load the cartridges, read the article HERE.

|

| Fig. 4: A batch of my replicated M1873 cartridges. |

As the article in the link above shows, I started with 35 grains of 3F powder, but since I want to replicate the M873 correctly I have switched to using only 30 grains. I believed that the 2F powder originally used in the M1873 cartridges would be less accurate since 2F takes longer to combust fully in a revolver barrel (which is why 2F is normally used for rifles while 3F is normally used for revolvers), so today's range session was intended to compare the two types of powder to see which was more accurate, and to see which came closer to the original in terms of muzzle velocity. Unfortunately, my chronograph gave obviously spurious results (ranging from more than 3,000 fps to under 300 fps for the same loads), so that determination remains to be examined. As to accuracy, however, my prediction failed, with the 2F and 3F having almost exactly the same accuracy, with the 2F being a very, very slight bit better (small enough to be within the margin of error of such a test).

Conditions: Lytle Creek Range, bright and sunny, 42 degrees, wind 9 mph (gusting to 22 mph) from 10:00, 52% humidity, barometer 30.08 inHg.

All shooting was done with my Colt 1860 Conversion revolver from a rest (to take the human factor out of the equation as much as possible) at 15 yards. All shooting was done at a 3 inch black dot using a full sight and a 6:00 hold without aiming off. I fired three tables of fire, with 12 rounds with 30 grains of 3F Schetzen, 12 rounds with 30 grains of 2F Schuetzen, and 6 rounds of 35 grains of 3F Schuetzen.

I used the String Test to gauge the accuracy of my shooting. To learn how the system works and why anyone doing historical shooting should be using this superb system to gauge accuracy, see the article HERE.

|

| Fig. 5: Table of Fire One. |

Table One: 30 grains of Schuetzen 3F.

12 rounds, string measurement 31.5 inches.

String Test: 2.6 in./rd.

|

| Fig. 6: Table of Fire Two. |

Table Two: 30 grains of Schuetzen 2F.

12 rounds, string measurement 29.5 inches.

String Test: 2.5 in./rd.

|

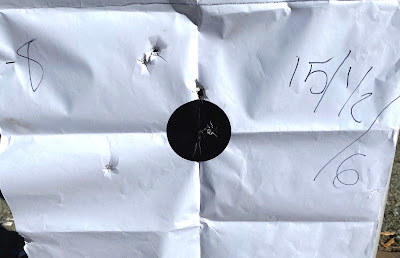

| Fig. 7: Table of Fire Three. |

Table Three: 35 grains of Schuetzen 3F.

6 rounds, string measurement 15.25 inches

String Test: 2.5 in./rd.

Conclusions:

My goals today were first, to see how close my replication of the M1873 cartridge was to the original, and second, to compare the accuracy of using 3F vs. 2F powder. Finer 3F powder has always been used for revolvers, with short barrels, because it is completely consumed sooner (contrary to popular belief it does not burn any faster than coarser powder) than coarser powder, while rifles, with long barrels, use coarser powder so the bullet is more gradually accelerated in an effort to reduce stripping (in which the bullet starts out too fast and so strips over the rifling). I expected that using 2F powder would mean that not all of the powder was fully consumed before the bullet left the muzzle, resulting in a lower muzzle velocity and correspondingly worse accuracy. That expectation was not realized. In fact, although I couldn't get my chronograph to work correctly and so couldn't compare muzzle velocities, I shot a third table with cartridges containing 35 grains of 3F just for comparison purposes, and got approximately the same accuracy with that load, indicating that the higher muzzle velocity it produces failed to provide any better accuracy. But then, that's the thing about science: You hypothesize, then you experiment, and your lovely, elegant hypotheses are often shattered on the harsh shoals of reality.

Check my blog soon for part II of this range session in which I practiced with my new Uberti 1860 Army revolver using Kerr combustible cartridges. I felt that this experiment with the .45 Colt cartridges was different enough to get its own blog post, however, which is why I split the study into two parts.

Information on the M1873 .45 Colt cartridge in this article comes from: Kuhnhausen, J. The

Colt Single Action Revolvers - A Shop Manual, Vols. I & II. Heritage

Gun Books, 2001.