I have created a video showing the process described below for .44-caliber combustible cartridges. It can be found here: https://rumble.com/v2b5e7s-making-combustible-paper-cartridges-for-cap-and-ball-rervolvers.html

And I also made a video showing how I make .36-caliber combustible cartridges which can be found here:

https://rumble.com/v2mvmjq-making-.36-caliber-combustible-revolver-cartridges.html

INTRODUCTION

Cap and ball revolvers can be loaded in different ways, the simplest of which is to pour a charge of powder from a flask into a chamber, add a ball onto it, and then force the ball down onto the charge with the pistol’s loading lever. Many bullet molds of the period included both a conical and a round-ball cavity in each mold, so round balls were certainly used, but by the 1860’s almost all military ammunition used conical balls (Ordnance Dept. 1861 p. 266).

Loading with loose powder and ball is extremely fussy and time consuming and carrying all of the components separately is awkward. Because of this, most Civil War pistol ammunition was issued in the form of cartridges. The first of these were made in the same way paper cartridges were made for the muskets of the period, viz., a non-combustible paper package containing the powder charge and a pre-greased bullet. These were loaded just as with loose powder and ball: the paper was ripped open and the powder poured into the chamber, then the ball was seated on top and driven in with the loading lever. This method was used for the first military-issued cap and ball ammunition, such as for the Colt Dragoon revolvers (Suydam 1979 p. 30).

Later, combustible cartridges replaced the musket style because they were faster and easier to load. When loading combustible cartridges the entire cartridge was inserted into the chamber as a single unit and then driven into place with the loading lever, which meant that reloading was significantly faster and easier than loading with loose powder or with the earlier type (id. pp. 31-32). Several styles were tried, including foil-wrapped cartridges, compressed powder cartridges, and skin cartridges (with intestine forming the shell), but in this article we will focus exclusively on nitrated paper cartridges.

These paper cartridges consisted of a paper shell, corresponding to the brass case of a modern cartridge, which was prefilled with powder and glued to a conical bullet. The paper was treated with a solution of potassium nitrate to make it burn quickly and completely when fired. The bullet was then dipped in grease to finish the cartridge.

Many millions of combustible paper revolver cartridges were manufactured by both sides during the Civil War, varying considerably from manufacturer to manufacturer with regard to bullet sizes and powder loads (see Thomas 2003). Thus, we cannot say any specific bullet or load is uniquely “correct” for the period, so the intention of this essay is to show the making of typical combustible cartridges. These choices do not reflect the only kind of cartridges made but should be representative of the cartridges of the period in general.

THE BULLETS

Pistol bullets were made by a number of different manufacturers during the Civil War, including Colt, Johnston and Dow, Richmond Laboratory, and more. Unfortunately, most modern reproduction revolvers are designed to fire round balls rather than conical bullets despite the fact that the latter were the norm in the Civil War. Because of this, some reproduction pistols are not well suited to firing conical bullets, either because the loading port in the frame is not large enough or because the rammer on the loading lever extends too far into the loading port or both (see Fig. 2).

|

| Figure 2: A picture showing how the rammer of the Pietta NMA extends too far into the loading port. |

Many of the bullets issued to Federal troops during the war will not fit into replica revolvers without extensive modifications to the weapon. Fortunately, Mark Hubbs of Eras Gone Bullet Molds (q.v.) discovered an authentic .44-caliber Civil War conical bullet design which will work in modern reproductions and created a mold for making them; this bullet was originally designed for the London Arms Company Kerr revolver (Hubbs 2020).

Thousands of Kerr revolvers were imported into the United States during the Civil War, the majority of which were smuggled into the Confederacy, and many Kerr paper cartridges and molds for bullets were imported as well so this was an extremely common bullet during the war.

|

| Figure 3: An original Kerr bullet (left) and a modern reproduction from Eras Gone Bullet Molds. Photo courtesy of Mark Hubbs. |

THE PAPER

Unfortunately, we do not know what specific kind of paper was used to make cartridges. Given the fact that rag paper was common during the period it is likely that was used, however, it almost certainly varied from manufacturer to manufacturer because the processes of the day were not standardized. We also know that a number of other materials, including foil, linen, and even dried animal gut were tried (Suydam 1979 pp. 31-33).

Many people use either cigarette papers or perm-wrap paper to make paper cartridges today because they are extremely thin and tend to burn completely without the need for any treatment. During the nineteenth century, however, when paper was used for cartridges it was nitrated to make it burn more quickly and completely. Nitrating paper means soaking it in a super-saturated solution of potassium nitrate (saltpeter) (id.). The potassium nitrate I used is simple stump remover purchased from Amazon; check the ingredients to ensure it's at least 90% potassium nitrate.

The paper I use is unbleached coffee filter paper which has been treated by soaking it in a concentrated solution of potassium nitrate and then drying it. Coffee filters are fairly thin, absorb the potassium nitrate solution well, and the unbleached paper is a close match in color when compared with extant examples. In addition, coffee filter paper is slightly heavier than cigarette paper, which is very important. Experiments with cartridges made from cigarette paper have shown them to be excessively delicate and liable to tear open very easily, which seems contraindicated for soldiers living and fighting in the field. The heavier coffee filter paper significantly reduces this problem, and while the thicker paper does require the nitration process to ensure complete combustion, doing so is quite simple and easy.

1. Heat two cups of water to the point of boiling.

|

| Figure 4: Soaking the filter papers in potassium nitrate solution; hanging the saturated papers to dry. |

Once dried, the papers can be stored for later use but be aware that they are now highly flammable so they should be stored carefully in a safe location away from any ignition sources. The potassium nitrate solution can be saved and reused.

MANUFACTURING THE CARTRIDGES

Paper cartridges were made by rolling precut paper around a mandrel and securing it with glue. The glue specified in the 1861 U.S. Ordnance Manual was a starch-based glue (p. 264) which was used because it burned easily. I use Elmer’s natural glue sticks because the starch-based glue in them has similar burning characteristics and they are much easier to handle than liquid glue.

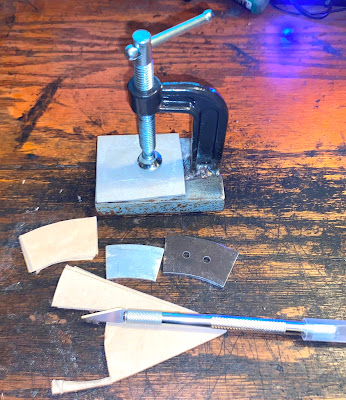

|

| Figure 5: Paper cartridge former by Capandball.com along with two formed paper shells. |

Forming the cartridges:

1. Fold the

filter paper so that several pieces can be cut at one time and use the template

to cut pieces from it for the bodies of the cartridges.

2. Use a nickel

as a template to cut disks from the filter paper to form the bases of the

cartridges.

3. Rub the

mandrel with paraffin and then rotate the mandrel in the base in order to

spread paraffin over the inside of the hole.

This will prevent the glue from causing the paper to adhere to the

former.

4. Wrap a cut

piece of the paper around the mandrel with the narrow end of the paper aligned

with the bottom of the mandrel, then glue the edge of the paper to close the

overlap.

5. Apply more

glue in a narrow band all around the bottom of the body of the cartridge while

it is still on the mandrel; the glue should only cover about one-eighth of an

inch of the paper.

6. Center one

of the cut disks of paper over the upper opening in the base of the former and

then insert the mandrel with the glued paper shell on it into the base of the

former and twist it to give it its final shape.

7. Remove the

mandrel from the paper, leaving the paper shell in the base.

8. Measure

twenty-five grains of black powder and pour it into the paper shell. Tap the

base lightly on a hard surface to settle the powder.

9. Apply a

small amount of glue to the rings at the base of a bullet, then insert the

bullet into the open end of the shell in the form. Press it down firmly to seat it and to

further compact the powder. Squeeze the

top edge of the shell to cause it to adhere to the bullet.

10. Remove the

finished cartridge from the former and again squeeze the top of the shell

against the base of the bullet with your fingers to ensure good adhesion. The finished cartridge will be ready to grease in a few minutes when the glue is fully dry.

|

| Figure 6: The templates laid out on the folded paper; the pieces cut and ready to form. |

|

| Figure 9: Waxing the mandrel. |

|

| Figure 15: The bullet glued into the shell. |

NOTES ABOUT CARTRIDGE MAKING

This takes practice. My first efforts were crude and practically

unusable, but I believe the ones pictured above to be quite acceptable. Since the coffee filter paper is heavier, it

makes the process easier than when using the thinner cigarette paper, which

often folds on itself or rips during handling. When wrapping the body of the shell on the mandrel it should be tight or else the paper will slide up on the mandrel and become too wide. Press the mandrel firmly into the base when forming the shell, and rotate it carefully to get a good shape, but do not use excessive force or the paper will tear. Rotating the mandrel when you insert it into the base will give the shell a crisper shape and make it easier to remove the mandrel because the paper often wants to remain on the mandrel when you try to remove it. Seat the bullet firmly in the cartridge when you assemble it because this will make the entire “package” firmer and more consistent. When removing the cartridge from the former, do so by pinching the paper shell right where it meets the base of the bullet because the glue will not be completely dry. If the bullet is not seated perfectly you can still work the edge of the paper shell up the side of the bullet slightly with a gentle sliding motion of your fingers when you first remove it before the glue is completely set.

Try to keep the grease from getting onto the paper because if it does it will increase the diameter of the cartridge at that point making it more difficult to load it into the chamber and may also contaminate the powder. Once the grease has cooled and hardened on the bullets the paper cartridges are complete and ready for use or packaging.

|

| Figure 17: Completed cartridges cooling after being greased. |

Weighing six greased cartridges showed a range of from 242.96 to 247.74 grains, with an average of 245.79; median: 246.22; and standard deviation: 2.29.

PACKAGING PAPER CARTRIDGES

During the Civil War manufacturers bundled paper cartridges into packs of six rounds each for distribution to the troops. During the early part of the War the packs were often nothing more than a sheet of paper wrapped and folded around loose cartridges and secured with a piece of cord, as shown in the picture below. These were primarily used for non-combustible paper cartridges (see Hubbs 2018 and Thomas 2003 pp. 22-23).

After the change to the more delicate combustible cartridges, cartridges were usually placed into pasteboard boxes (e.g., see Thomas 2003 pp. 50-51) or else in light wooden blocks which had been drilled out to hold each round separately, with the blocks then wrapped with paper (e.g., id. p. 140). Often a string or wire would be glued to the block and left to hang outside of the wrapped paper to use for tearing the package open (Hubbs 2019). The wrappers were often painted with varnish in order to keep the cartridges dry (Thomas 2003 p. 20). Examples of this type of block can be seen in the pictures below.

|

| Figure 19: Two wood-block paper cartridge bundles, one opened and the other still wrapped. The split-style box was unique to Colt ammunition, most blocks were not split. |

|

| Figure 20: A drawing from the period by General John Pitman showing a cartridge block. |

These packages were shipped in wooden crates and then issued to individual soldiers, who would carry them either in purpose-built leather cartridge pouches, or, when belt space was at a premium, in their pockets, knapsacks, haversacks, etc. Mark Hubbs of Eras Gone Bullet Molds pointed out that a cavalry trooper had a pistol holster, a carbine cartridge pouch, a carbine cap pouch, and a saber on his belt, which, given the average waist sizes of the day, left little room for an additional pistol cartridge pouch. This would have been less of a problem for officers in other branches since they wore less on their belts.

The cartridge pack kit used for this project was purchased from The Tube Factory at Etsy.com, and came with precut and drilled wooden blocks, preprinted wrappers, and pieces of hemp string. These kits normally include paper cartridge tubes for making blank cartridges for Civil War reenactment, however, I elected not to get them since I was making my own.

Making wood-block cartridge packets:

1. Insert six

cartridges into the holes in the block, bullets up.

2. Wrap the

hemp string around the wooden block just below the top edge so that one end

sticks out to the side and glue it down with a glue stick. Allow the glue to dry.

3. Lay the

wrapper face down, then position the block on the wrapper so that the printed

text will be centered on the block when finished.

4. Fold the

bottom of the wrapper up over the block, then fold the top of the wrapper over

that so that the top overlaps the bottom.

Apply glue to the bottom edge of the wrapper and press the top edge onto

it, ensuring that the wrapper is tight.

Allow the glue to dry (try not to glue the paper to the block at any

point so that it will be easier to reuse the block).

5. Fold the

sides of the wrapper on the edges of the block as you would to wrap a Christmas

present and glue them in place, trimming

them as necessary to make a tight fit.

Make sure the loose end of the string sticks out from the wrapper by

about two inches.

6. If desired,

paint the entire cartridge packet with clear varnish to waterproof it (this was

not done for this project since weather was not an issue and not varnishing the

packages has no effect on shooting).

|

| Figure 21: All of the components for a cartridge packet. |

|

Figure 22: The cartridges inserted into the block. |

|

| Figure 23: Gluing the string. |

|

| Figure 24: Gluing the body. |

Figure 25: Gluing the ends.

Figure 26: The completed cartridge bundle (note that the label does not match the bullets used here).

An additional note about cartridge packaging: Mark Hubbs was kind enough to share the pictures below of an extant Kerr paper cartridge produced by Eley Company of London. These pictures show an additional outer wrapping of paper around the paper cartridge, presumably for protection against water or physical damage. While this outer wrapper was not attempted for this project, John Crossen of Crossen Cartridge Formers has worked out a method for replicating this wrapper, and I will be trying it soon.

|

| Figure 27: Kerr paper cartridge mfd. by Eley Co. of London and the base showing the maker’s name. Photos courtesy of Mark Hubbs. |

Figure 28: Getting ready for the range--.44 and .36 cartridge packets.

PERCUSSION CAPS

Percussion caps are small formed cups made of very thin

metal which are placed over the nipples of a revolver. They are filled with an explosive mixture

made from fulminate of mercury and potassium nitrate which will detonate when

struck sharply. The nipples are pierced

to allow the flame to pass from the cap through to the chamber to ignite the

cartridge.

Remington #10 caps were used for this study as they fit best on the Pietta Remington NMA pistol used. A reproduction cap tin modeled after period pieces was used to store the caps for this project; since Eley manufactured Kerr bullets during the war, and since this example mentions both Eley and Remington revolvers, it is particularly well suited to this project.

- Hubbs, Mark. “Civil War Revolver Cartridge Pouches.” YouTube, uploaded 20JAN2018, youtu.be/0hC1r_ad1Zc.

- ———. “Making Authentic Sharps Carbine Cartridges.” YouTube, uploaded 28APR2019, youtu.be/1ggj_uPEXiU.

- ———. “The Eras Gone Kerr 44 Bullet.” YouTube, uploaded 03042020, youtu.be/GDtYhG4vKqc.

- Macdonald, K. Dale. “M1860 was Colt Most Used by Civil War Combatants.” The American Rifleman, February 1972, pp. 33-35.

- Németh, Balázs. “Remington vs. Colt revolvers firing Johnston & Dow Bullets.” YouTube, uploaded 26JUL2017, youtu.be/5AThglFR5N4.

- United States Ordnance Department. The Ordnance Manual for the use of the Officers of the United States Army. Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott, 1861.

- Suydam, C. R. “Pre-Metallic Cartridges for Pistols and Revolvers.” American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin, Bulletin #40, Spring 1979, americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/1979-B40-Pre-Metallic-Cartridges-For-Pistols-And-.pdf. Accessed 19OCT2021, p. 30.

- Thomas, Dean S. Round Ball to Rimfire: A History of Civil War Small Arms Ammunition. Part Three, Federal Pistols, Revolvers & Miscellaneous Essays. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2003.

This is great information. I can't wait to try it!

ReplyDeleteThank you.

DeleteThank you.

ReplyDeleteThose wooden cartridge blocks are too big......as are many that I see available. The ones in your photos can easily be sanded smaller, almost to the holes.......compare to the original that you show.

ReplyDeleteYou are correct, however, the difference is very small, and I can fit two of the cartridge packs into my cartridge pouch, which is as it should be for the .44's, so I am not terribly concerned about it. I think the maker made them a bit thicker to make them hold up better for multiple uses by reenactors--the very thin ones are quite delicate.

Delete