The equipment needed or desired by a historical shooter is largely a matter of personal taste and interest; the kit chosen can be as simple as just a weapon and ammunition or can be as elaborate as a full military uniform and equipment as for a living history presentation, or anywhere in between. In this post I will review the gear I have assembled for my personal kit as an example of what the reader may wish to consider. Obviously, this is a work in progress and will need a lot of work to bring to the standard I hope to achieve.

While I do not intend to participate in a nineteenth-century living history group, I elected to pick a specific campaign in which the Snider played an important role as a way to focus my choices in a consistent way. I chose the Abyssinian campaign of 1866-1868, and specifically the Battle of Magdala, because that was the first time the Snider played an important role in the warfare of the period. For even more precision, I chose the 4th King’s Own Royal Regiment as my unit since they were one of the first in contact. For others of a like mind I heartily recommend reading Stanley’s Magdala: The Story of the Abyssinian Campaign of 1866-7. For an excellent exemplar of a soldier from that campaign, look at the picture of a private of the 4th Foot shown below which was taken during the Abyssinian campaign. As the photographs of the period make plain, by this point in history soldiers rarely wore knapsacks in battle, they being carried in the unit pack train instead. For that reason I chose to forego the knapsack and assemble the rest of the kit appropriate for a soldier in that battle; we might term this kit “Field Order.”

|

| A Private of the 4th Foot in Abyssinia. |

|

| My full Abyssinian Campaign uniform. |

|

| Drill Order uniform. |

E

The air-tube helmet shown in the picture of a soldier of the 4th Foot came about because British designers were seeking a way to make a helmet suited to the heat of their foreign conquests. Harry Elwood of Elwood and Sons came up with a so-called ‘air chamber principle’ for hats. I have recently acquired a reproduction air-tube helmet made by a friend, but the example in the older pictures above is a modern reproduction of a later foreign-service helmet.

Information about the uniform worn in the Abyssinian campaign is somewhat limited, however, this was the first instance of khaki (or “kharki”)—a gray, tan, or brown fabric made of closely twilled linen or cotton—being officially issued to British troops (Farwell 1989 p. 75). This was the standard white drill uniform of 1859 dyed khaki in color (Barthorp 1988 p. 45); the jacket has a standing collar and five buttons, and the trousers are supported by braces. The uniform had a loose, comfortable fit well suited to hot weather. Although people today usually think of khaki being a brownish color, the color of such uniforms varied widely, and it is likely those worn by the 4th Foot were a sort of bluish gray (Barthorp 1994 p. 20). Unfortunately, no one carries the blue-gray khaki of the period, so I ordered a replica uniform from Regimental Quartermasters (regimental-quartermaster.com/index.html). The shirt pictured below comes from The Replicators in India.

|

| Standard British military shirt. |

The ball bag was used to carry a rag, the oil bottle, and

ten rounds of loose ammunition (id. p. 49). The cartridge pouch was modified

from the previous model by removing the cap pouch and by modifying it to hold

50 rounds of wrapped Snider ammunition in two tin dividers along with a

compartment for the Snider combination tool (id. p. 63). My load bearing

equipment comes from Graham Humphrey.

|

| My waist belt, ball bag, and bayonet. |

|

| Interior of the ball bag showing ten loose rounds, an oil bottle, and a rag. |

|

| The oil bottle. |

|

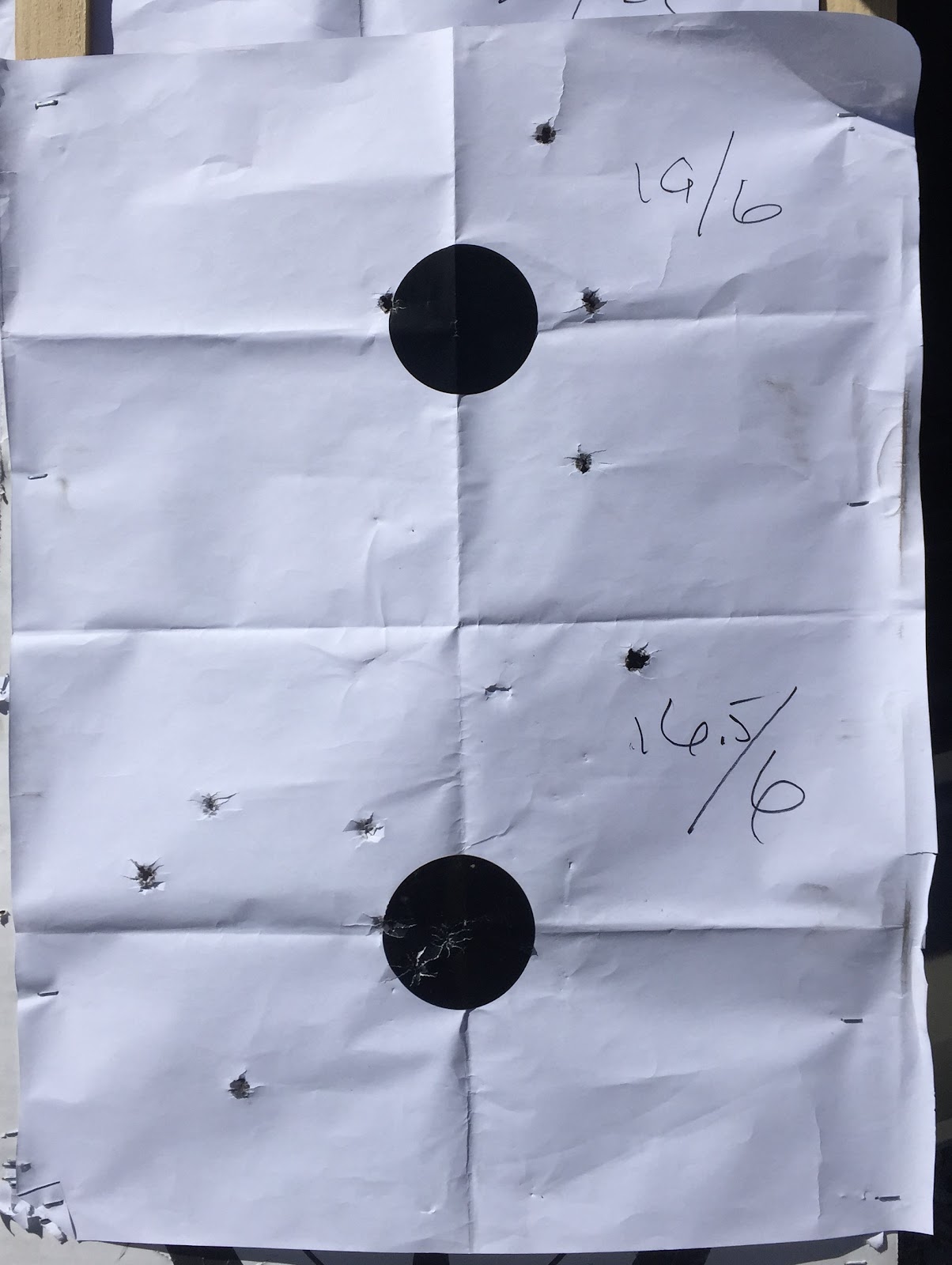

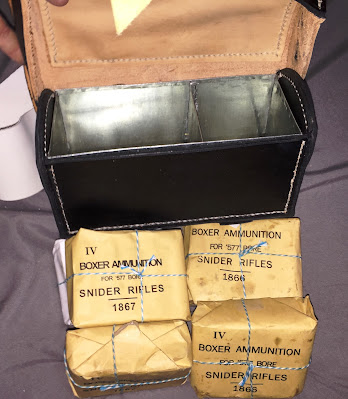

| My cartridge box with 50 rounds of wrapped ammunition. |

|

| Fifty rounds in the cartridge box. |

|

| The implement compartment under the lid of the cartridge box. |

|

| The cartridge box, closed. |

|

| My Indian Mutiny-style water bottle. |

The pattern-1867 haversack was made of linen or cotton and was changed from the previous versions by adding a sliding buckle to make the shoulder strap adjustable. In addition, this pattern had a button on the back so that when not in use the bag could be rolled up and buttoned (Turner 2006 p. 25). Although the haversack was normally used for the food ration, I use mine for shooting supplies such as a cleaning kit, target markers, notebook and pen, etc. My haversack comes from Regimental Quartermasters.

|

| My haversack, shown open. |

|

| My haversack buttoned up for carry when empty. |

My Snider is a Mk. III model made in Nepal in 1868, and thus it is impossible that it should have seen service in Abyssinia. Rather, the rifles used at Magdala were almost certainly Mk. II’s, although, again, I am perfectly content with this anachronism. I purchased my rifle from a private collector. Since Sniders were converted from the earlier 1853-pattern Enfield rifle (and even the new-built Mk. IIIs were of precisely the same design at the muzzle), the 1853-pattern bayonet and scabbards were still in use. My bayonet is from 1864 and was used during the American Civil War, but the scabbard is a modern reproduction. They were purchased from a private collector. The rifle sling used in the Abyssinian campaign was probably the 1850 pattern with a buckle on the rear, however my sling is the 1871 pattern which was the last buff-colored version and was attached with a leather thong rather than a buckle (id. p. 44), which was the type used on later Sniders such as mine. My sling comes from Pierre Leather. The ammunition carried was made with a mold sold by X-Ring Services using brass from the same company.

|

| My Enfield bayonet. |

|

| Finished Snider cartridges. |

Nota bene: Of course, if I were an actual Snider "rifleman," I'd have a two-band Snider and my leather gear would be black. I hope my readers will appreciate the linguistic nuances of my word choice for the title of this essay.

WORKS CITED

Barthorp, M. and D. Anderson. The British Troops in the

Indian Mutiny 1857-59. London: Osprey Publishing, 1994.

Barthorp, M. and P. Turner. The British Army on Campaign 1816-1902 (3): 1856-1881. London: Osprey Publishing, 1988.

Farwell, Byron. Armies of the Raj: From the Mutiny to Independence, 1858-1947. New York: W. W. Norton, 1989.

Stanley, Henry M. Magdala: The Story of the Abyssinian Campaign of 1866-7. London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Company, 1896.

Turner, Pierre. Soldiers’ Accoutrements of the British Army 1750-1900. Wiltshire: The Crowood Press, 2006.

SUPPLIERS

Stan Dolan, Regimental Quartermasters <www.regimental-quartermaster.com/>

Graham Humphrey, Graham the Leather Guy <grahamtheleatherguy@gmail.com>

Martyn Robinson, X-Ring Services

<xringservices@yahoo.com>

Le Pierre Sutler <www.lepierreleathers.com/>