A blog about historical shooting with black-powder firearms of the nineteenth century.

Tuesday, April 20, 2021

Loading Ammunition for the Mark IV Martini-Henry Rifle

Saturday, April 10, 2021

Range Report 4/10/21--Remington New Model Army Revolver

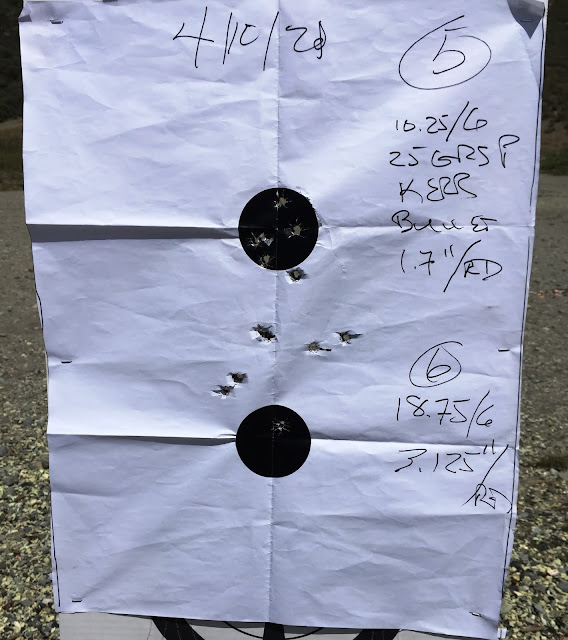

I fired my Pietta Remington New Model Army revolver at the range this weekend. I shot four Tables of Fire for actual score (not counting some casual plinking) using historically accurate .44-caliber paper cartridges with hand-cast Kerr bullets I made using a mold from Eras Gone bullets. The cartridges contained 25 grains of Pyrodex "P" (3F equivalent). To see how I made the cartridges, read this.

I measured the accuracy of my shooting using the historically accurate String Test Measurement that they used during the Civil War. This system compares the group of shots to the intended mean point of impact to give a result which is much more valuable and informative than merely looking at the size of the group as many shooters do today. The String Test is described and explained here.

I got some mixed results, with some groups being about average for my shooting, but with two extraordinary scores that far exceed what I have been achieving lately. I am at a loss to explain the differences--they may just come down to an old man getting sloppy some of the time, then buckling down to focus.

All tables were fired offhand using a full sight and a 6:00 hold at 15 yards. The bullseyes in the picture above are 3" in diameter.

Table One:

6 rounds, 18" string: 3.0 in./rd.

Table Two:

6 rounds, 11.75" string: 1.95 in./rd.

Table Three:

6 rounds, 10.25" string: 1.7 in./rd.

(This is the target at the top of the page in the picture above.)

Table Four:

6 rounds, 18.75" string: 3.13 in./rd.

(This is the target at the bottom of the page in the picture above.)

Heretofore I have been averaging about 3.2-3.6 inches/round, but Table Three above represents by far my best shooting to date, and even Table Two significantly exceeds my all-time best of 2.2 inches/round previously. I hope I can continue this trend. I recently acquired some Swiss 3F powder, and I look forward to seeing how this vastly superior product affects my scores--I have to use up the remaining hundred or so paper cartridges I already made first, however!

I have to say that I absolutely adore the Kerr bullets. They fit my revolver beautifully, they shoot extremely well, and my inner history geek loves having such a historically authentic bullet available. I am very thankful to Mark Hubbs of Eras Gone Bullet Molds for making the molds for these available.

Range Report 4/10/21--Martini Henry Mark IV

Finally, after long months of hassle and effort, I got my beloved Mark IV Martini-Henry rifle to the range. I only made ten rounds of ammunition because I wanted to see how it performed before loading the rest of it just in case I was doing something wrong. The rifle, made by Enfield in 1886, came from IMA of New Jersey, and I cannot say enough good things about my dealings with them.

The cases were formed from Magtech 24-gauge brass shotgun shells by Martyn Robinson at X-Ring Services. The bullets are hardened lead, paper patched, 540-grain, 0.468" and were made by Blue Falcon Bullets (they can be found on Gunbroker.com). I loaded them with 85 grains of Swiss 1.5F black powder, which is a very close match in performance to the R.F.G.2 powder of the originals. I used one-quarter of a cotton wad as filler, then put in a waxed card disk, followed by a one-quarter-inch thick "grease cookie" made of equal parts beeswax and olive oil, followed by two more waxed cards, followed by the bullet. I loaded the cartridges using a custom Martini-Henry die set also purchased from X-Ring Services. I followed the loading procedure demonstrated here by Rob Enfield of British Muzzleloaders.com. I believe this process resulted in an almost exact match for the drawn-brass cartridges as issued in period.

I fired all ten rounds at a target 18" wide by 23.25" high with a 3 inch bullseye at 100 yards from an offhand position. I used a half-sight picture and a 6:00 hold. This is a picture of the target (the extra holes on the paper are the result of a neighbor on the firing line with a shotgun who couldn't keep his fire in his own lane):

|

I first calculated the String Test Measurement to judge my overall accuracy. That procedure is described in full here. The string measurement was 46.5", which, divided by the number of rounds, gives a measurement of 4.65 inches/round--good enough to qualify for a Berdan Sharpshooter unit in the Civil War (had I done it with a muzzle-loading rifle and at 200 yards instead of 100).

I then determined the precision of the rifle and load by determining the Figure of Merit or "mean radial deviation," the same procedure used during the Victorian era for determining the precision of a weapon and its ammunition. The procedure for calculating is described in full here. I used the spreadsheet system created by Rob Enfield as discussed in the link above. This yielded a Figure of Merit of 4.39, and a group size of 15.92". The Grouping Diagram shown below is taken from Mr. Enfield's spreadsheet.

Conclusions

Range Report 15FEB2026: .45 Caliber Rifle Shoot Off

My Martini Henry and Springfield Trapdoor with correctly packaged ammo. People often like to compare Snider-Enfields to Trapdoors since they...

-

It occurred to me that it would be useful to have a single linked page that I can give people to show them where to get all of my books. I ...

-

I recently acquired a Pietta reproduction of the Remington New Model Army (not 1858, please !!) with a 5.5 inch barrel. Unusually for me, t...

-

My 1896 Krag Jørgenson and Mills Belt I was recently fortunate enough to acquire an 1896 Krag Jørgenson rifle in nearly pristine condition...